I Climbed Mount Kilimanjaro

If you had told me a year ago that I would climb Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, Africa I would not have believed you. It’s not that the 19,341 foot peak requires mountain climbing skills that I do not have, but it just was not on my list of things to do. I guess I can thank Emily for that.

We met a year ago, while both visiting a National Park in Alaska. We have since been camping and hiking in four other National Parks. While visiting Tanzania last fall on safari, Emily was inspired by the snow-topped mountain on the equator. Her safari driver had been a Kilimanjaro porter and he convinced her that she could do it. Upon her return, she asked me if I wanted to join her. I said yes, but not really thinking through the magnitude of the journey. At least I had eight months to prepare.

There are a lot of superlatives about Kilimanjaro. It is the tallest mountain on the African continent, making it one of the world’s seven summits. It is the world’s largest free-standing mountain. And most relevant to our climb, it is the highest point you can get to on Earth by hiking. I repeated this line many times as I told people about my trip. I told them that oxygen levels at 18,000 feet are half of that at sea level. The summit is more than 1,000 feet higher than that.

The altitude is the most dangerous part of the climb. Many people don’t make it because of altitude sickness. We chose an eight-day route because of the extra acclimatization time it provides. The guide company touts an 85% summit success rate for this eight day route. That means the 15% of the people still don’t make it. Two of the eleven climbers in our group might not make it to the summit. It was the guides’ job to get us all there, but it was more important to make sure we were all healthy enough to do it.

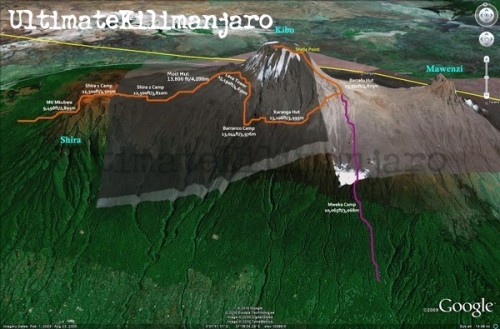

Kilimanjaro is a volcano that last erupted 150,000 – 200,000 years ago. It has three distinct volcano cones: Kibo, Mawenzi and Shira. The summit of the mountain, where most climbers go, is on Kibo. Mawenzi is a separate peak that you see off in the distance. You need a special permit to climb that, as well as mountaineering skills. And Shira collapsed, so now it is a plateau.

Day 0

One of the best running jokes of the trip came from Tom, an American construction manager who had been working in for a mining company in Liberia. It drove him crazy that the ground floor in European (and African) buildings is called floor zero. You have to go up a flight of stairs (or two) to get to the first floor. You don’t count starting with zero, he said. You start with one. He frequently argued his point, and any time something came up with numbers, we looked at Tom and tried to convince him that we start counting with zero.

Tom’s hiking companion was Wing, a conservationist who also works for the same mining company in Liberia. She is from northern England, and as the only European on the trip, she was the only one who really understood the whole ground floor as zero thing.

So it is only fitting that we begin this trip on Day 0, although we did have a prep meeting at our hotel on the night before the hike. We met the five guides that would be leading the 11 hikers. Robert was the lead guide. Someone asked him how many times he climbed Kilimanjaro and he said that he stopped counting. He climbed for two years as a porter and nine years as guide. And on average he took about 20 trips up per year. That’s well over 200 times. He was assisted by Baracka, Vincent, Jerome and Elias. These were the men we were counting on to get us to the top of the mountain.

Our first health check occurred during this meeting. They needed to check our pulse with a finger monitor. The device also checked the oxygen saturation of our blood, but that was not relevant at low altitudes. A resting pulse of less than 100 bpm was required to climb that mountain, as our pulses would increase at higher altitudes. We all passed.

As you read through the details of each day below, you’ll see a picture of me and Emily at the start of each hiking day. I’ve also included our start and end points for the day, elevation of each, distance hiked and the time it took. Several days had multiple destination, which I listed as separate hikes.

Day 1

from Lemosho Gate (6,890 ft) to Mti Mkubwa (9,498 ft)

4.35 miles

2:00 hours

The first official day of our climb began by climbing on a bus after breakfast. We left our hotel in Moshi and had a two-hour bus ride to the entrance of the park and registration. Mount Kilimanjaro is a national park and every climber must register at the entrance and at the official camps along the way. Along the drive we had a great view of the mountain from the bus. It looked pretty imposing. That is called prominence in mountain terms, where you see a significant amount of the face of the mountain.

But before we even got to the park we stopped in a small commercial district to purchase meat for the trip. If you are going to carry meat into the the wilderness for eight days without refrigeration, you may as well make sure it is as fresh as possible. But this was a third world butcher shop, so fresh does not quite mean what it means in a US supermarket. Emily had already opted out of all meat and requested vegetarian meals for the whole trip. I only ate meat sparingly.

We also had to pick up one more porter in town. We had a total of 39 porters on the trip. They were the ones who carried our stuff, the tents and all the other equipment to move our group up the mountain. There were also two chefs who would prepare all of our meals. That’s a total of 46 people supporting 11 hikers for 8 days of hiking. The impact of this is pretty significant on the mountain. And this is only one trip from one touring company. This is why access to the park is tightly regulated.

After registering, we had a box lunch and we still had another 30 minutes to drive before we reached our starting point, the Lemosho Gate. We had been preparing for this trip for so many months and I was ready to get hiking. We arrived, got off the bus and were ready to go. We hit the trail around 2pm. The porters were still organizing our stuff, but like every other day, they would pass us by, carrying gear on their heads.

Our eight-day hike started on the western side of the mountain. This first day was in the rainforest. Luckily it was very dry, so it just seemed like a dense forest. This was a long, slow climb. Parts of the trail were steep enough that we were climbing steps. Lots of steps.

One of the first words of Swahili that all Kilimanjaro hikers learn is pole pole (pronounced po-lay po-lay). It means slowly. Even from this first day we started at slow pace.

Over the course of this hike we went from under 7,000 feet to nearly 9,500 feet above sea level. On this very first day I had already gone higher in elevation than I had ever been. And I was already starting to get a slight headache. This did not bode well for the trip. One of the ways to reduce the effects of altitude is to stay well-hydrated. One of the by-products of staying well-hydrating is that you have to pee a lot. And let me warn my gentle readers that there will be a fair amount of discussion about bathroom habits in this story. It comes up a lot on an eight-day hiking trip.

After only an hour of hiking I had to step off the trail to get rid of some of that water I was drinking. Normal hiking etiquette requires you to take several steps off the trail and hide yourself behind a tree. That definitely was my approach to this personal bathroom break. I got winded catching up to the rest of the group.

Another of the first Swahili words we learned was jambo, which means hello. Many of our porters did not speak English. As they passed us on the way up to our first camp, we greeted them with a reluctant jambo. It was hard to find the right balance communicating with some of the porters. We carried day packs. They carried our 30 pound duffel bags, tents, sleeping bags, cooking utensils, tables and chairs. Much of it on their heads. We did get friendlier over the course of the week and our jambos got heartier as they passed us.

Porter (Photo by Bill D)

We made it to our camp in the woods. The porters had all passed us, got to the campsite and set up camp. We settled into our tents and got ready for dinner. Every night about a half hour before dinner, they put out “water for washing.” This was warm water in our own basin with a little soap. This felt like a transition from the real world. Early in the trip, we took advantage of this, but as we climbed higher and the temperature got colder, this just didn’t seem to be that important.

First campsite (Photo by Bill D)

Meeting the porters (Photo by Nate)

I kept track of every meal we ate, but that seems to be way too much detail for this post. But just to give you some idea about the food, this dinner, and every other lunch and dinner began with soup. This first night it was spicy zucchini soup. Other meals had carrot soup, cucumber soup and vegetable soup. It was good, but all these soups starting running together and I just couldn’t stomach any more soup. We also had vegetable stew, potatoes, salad and fried fish. We were glad they served the fish on the first night, rather than waiting even until the second night.

I didn’t have much of an appetite, which is one of the signs of altitude sickness. But it was more that I had no taste for anything. Things just didn’t taste right to me, so I didn’t feel like eating. After dinner was our first health check on the mountain. My pulse and oxygen levels were fine. In addition to checking those, the guides asked each of us the same questions.

- Do you have a headache?

- Any dizziness?

- How’s your appetite?

- Are you abnormally tired?

Based on my answers to these questions, I was given 5 points. Because in addition to having a headache and not much appetite, I was tired because I didn’t sleep well in the hotel the previous night. If I had been given 6 points, I would not have been able to continue. So if this were the reality show of our climb, you would already be concerned about me making to the top.

Collubus monkeys chattered in the trees above us (Photo by Bill D)

Here on the equator, the sun goes down at 6:30pm. If you have ever been camping, once it gets dark, everyone heads back to their tents and gets ready for bed. Once dinner, health check and our discussion about tomorrow’s plans were done, it was time for bed. It was also medication time. Ibuprofen for my headache and imodium for my stomach. I had not planned on taking diamox, which helps your body adjust to attitude, but based on how I felt, I started taking that too. That is a twice a day pill and the main side effects are tingling in your extremities and excessive urination. If something was going to make me pee more on this hike, I was definitely in trouble.

Since I had not slept that well the night before, I was expecting to get to sleep pretty easily. That was not the case. Anxiety, intestinal rumblings and all that water I had drunk did not help me get to sleep or stay asleep. I was concerned that I would not be able to continue. If I felt worse from the altitude in the morning, I felt like I should go back. It was only a two-hour hike back to the park entrance. If I waited until the next day to see how I felt, the return hike would have been much longer. I also felt like I was unprepared for the trip because I was running out of hand sanitizer. These were definitely the nighttime ramblings of a sleep-deprived person.

Oh yeah, remember I said that we’d be talking a lot about bathroom issues. Well, there were no qualifying questions during the health check about how my intestinal tract felt and was all that normal. It was not. This started on my way to Africa and was continuing up the mountain. If you are still thinking about the reality show version of this trip, you would have seen grainy, nightvision video of me getting up and going to our private toilet tent, affectionately known as Peter’s Paradise, seven times during the night. Hikers in the closest tent heard every trip I made.

Peter, the porter responsible for carrying and maintaining our private toilet, outside Peter’s Palace (photo by Nate)

Day 2

from Mti Mkubwa (9,498 ft) to Shira 1 Camp (11,500ft)

4.97 miles

5:40 hours

We woke up after our first night on the mountain a little worse for wear. Normally I would not share a blurry photo, but it really does express how we felt that morning. What I didn’t know when I was getting up all those times was that Emily was not sleeping well either. The sleeping pads provided by the tour company were not that comfortable, and definitely not as advertised as “better than any commercially available sleeping pad.”

Again, since we were near the equator, we had equal parts of daylight and night time. That meant that the sun came up around 6:30. That was also our wake-up time. And we had to be in the mess tent by 7:00.

I was feeling a little better, but I began the day with a morning drug cocktail. In addition to the ibuprofen, imodium and diamox, I had my daily malaria pill to take. Just like almost every lunch and dinner began with soup, we learned that every breakfast began with porridge. Oranges, papaya, eggs, sausages and toast rounded out the menu.

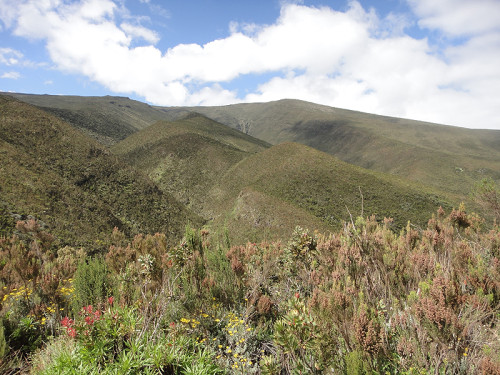

It was a little hard to get ourselves together and moving after this first overnight, so we hit the trail around 8:20. The first part of the trail continued through the forest. As we went higher and higher the vegetation got shorter as we crossed into what is called the moorland. We eventually came out into the open and we could see the rolling hills around us.

Due to the length of our hike, we couldn’t wait until camp for lunch, so we had a box lunch. For some of us this was our third day in a row to have a box lunch. It included a cheese and carrot sandwich, a piece of chicken, a hard boiled egg, cookies, peanuts, a muffin and a juice box.

Nate and Bill S are aerospace engineers. Bill D is a high school history and geography teacher. All three are from Atlanta, although Bill D has since moved to Missouri. They periodically take big trips like this together. While in Alaska several years earlier they planned to climb Kilimanjaro. (Photo by Bill D)

We reached the Shira Ridge, which is the third volcanic cone that makes up the mountain. It had collapsed further than the other two cones. We had crossed into the sub-alpine desert and we were now seeing evidence that we were indeed hiking up a volcano. We reached our camp around 2:00pm and everything was set up and ready for us. There was plenty of wide open space to explore and plenty of time before dinner.

There was also a large stream running along side the campsite. Robert, our lead guide, pointed across the stream and towards the clouds and said that the peak of the mountain was right over there. And by 6:00, he said, the clouds would clear and we would be able to see it. And he was dead-on. The clouds started breaking up around 5:30 and by 6:00 it was totally clear. After two days of hiking, we could see our destination. And it looked amazing.

I felt a whole lot better by the end of our second hiking day. And after my disastrous result during the health check the day before, I was determined to answer those questions in a positive manner. We even started joking about getting points through our actions. No napping allowed or you would get points for excessive tiredness. I was off the list of the least likely to make the summit.

But Emily, a doctor who knows how to take her own pulse, and has been at high altitude, has test anxiety. So even though she can take her pulse while resting in the tent, and it is well below the acceptable limit, once the pulse meter is put on her finger, her anxiety level drives her pulse higher. And there’s nothing she can do to bring it down. The anxiety is caused because the guides can tell her she can’t climb further, even though she knows she’s fine. This was an issue throughout the week, whether she went first, last or somewhere in the middle. Thankfully, it never became a real issue, but you could tell that guides were uncomfortable with her elevated pulse.

We had been on the trail for two days with no cell phones or other comforts of home. I realized that I had not looked in a mirror for two days. It would be another six days before I saw what I looked like. My appearance was not changing much, although my beard was growing each day. Even without being vain you see your reflection in the mirror several times a day. I could make some tenuous connection to the idea of identity being wrapped up with seeing your image, but that’s probably a stretch.

Emily started knitting a hat that she would wear on the summit climb. A hat is just made of ever decreasing circles and you tie it off at the top. I was disappointed that it would not include a pompom on top.

That night I had one of the best night’s sleep I had in a long time. Even though I got up a couple times during the night to use Peter’s Palace, I slept longer than I do at home. The night sky was beautiful. The glaciers on the summit were highlighted by the moon. Loads of stars, including a view of the Milky Way after the moon went down.

Day 3

from Shira 1 Camp (11,500 ft) to Moir Hut (13,800 ft)

4.35 miles

5:35 hours

We woke up at 6:30, sunrise, and we were starting to establish a morning routine. Wake up, wash, breakfast, pack up and leave. It took us a little longer to leave camp than our guides wanted. If we packed up before breakfast, we were late for breakfast. If we waited until after breakfast, our crew was anxious to pack up and leave, so we were kind of rushed. We didn’t hit the trail until nearly 8:30.

Our Swahili lessons were continuing as we hiked. Twende means let’s go. It was not really a battle cry, but a way to get going. Our call and response words went like this. “Hip Hip,” said the guides. “Hop Hop,” we said. “Don’t stop,” they said. “To the top!” was our answer. We always started with this and it was the way we could power though the hike if things were dragging.

The mountain peak came out from behind the clouds before sunset the night before and remained out all night. It was still visible in the morning when we left. The sun was out. The sky was blue and we were walking towards the mountain as we were coming out of the sub-alpine desert. It was so prominent and we walked towards it all day that it didn’t really seem like we were making progress.

The vegetation was changing, getting smaller and heartier as we were making our climb another 2,000 feet up the mountain. This was long gradual hike that seemed pretty easy. The altitude was no longer bothering me, even though I was now several thousand feet higher than I had ever been.

If you are a woman and you have ever been hiking, then you know that stepping off the trail to pee is not the easiest thing to do. But what if you could pee standing up, and without dropping your pants all the way? Before the trip Emily purchased a pstyle so she could do just this. She picked it because it had the best reviews and it gets her highest endorsement. It made things much easier on the hike. She never had to use it in the tent (we had pee bottles that went unused), so I have no information how it works in enclosed spaces. She had a blue one.

This was the heart of the climb where we would stay at around 13,000 feet for a few days to help our acclimatization, as well as go higher a couple of times and come back down to this altitude. While that doesn’t even temporarily change how your body deals with limited oxygen, it does let you experience those higher altitudes.

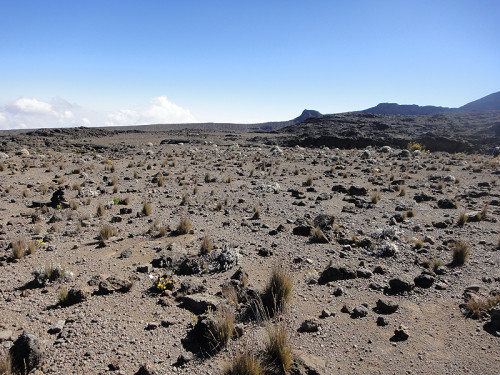

The terrain was also becoming rockier. This was a dormant volcano and there are two types of rocks that you see on a volcano. There are the big ones that fly out of the erupting volcano and then there are the ones formed by hardening lava flows.

Nigel is a crocodile farmer from Zimbabwe and his son, Keith, is a financial planner who lives in Chicago. Climbing to 19,341 feet may seem like a cake walk when you deal with 150,000 crocodiles every day. (Photo by Bill D)

We arrived at camp around 2:00 and had a late lunch. Today was the day that we had an optional hike to prepare for some altitude. At around 4:30 we left camp and began hiking upwards. The terrain was dirt and loose gravel. This would be similar to the day we summit. Except it would be dark, colder and many hours longer. We hiked up about 500 feet and from our vantage point we could see the mountain peak in one direction and we could see that we were above the clouds.

Dinner began with soup, as usual, but this was one of the rare times that we had dessert. It was banana fritters and they were magical. None of us ever went into the cooking tent, so I have no idea what the chefs cooked with, or how they made anything, but they had the ability to fry food.

Each night after dinner Robert, our lead guide, tried to teach us how to count in Swahili. He was doing it three numbers at a time. Since it was day three, we were already up to nine. Most of us couldn’t even remember 1-2-3 at this point.

1-2-3: moja, mbili, tatu

4-5-6: nne, tano, sita

7-8-9: saba, nane, tisa

Clear skies continued through the night. The moon was getting fuller each night and again the glaciers on the top of the mountain looked beautiful as they reflected the moonlight.

Day 4

from Moir Hut (13,800 ft) to Lava Tower (15,190 ft)

2.49 miles

3:15 hours

from Lava Tower (15,190 ft) to Barranco Camp (13,044 ft)

4.35 miles

2:30 hours

We slept in a bit this morning and didn’t leave camp until 9:00. This meant it was little warmer by the time we left. Morning routine was becoming even more routine and we had all figured it out. We didn’t even really miss our showers at this point. Some personal cleansing with some wipes was good enough until the next morning. We were hiking through the high desert today. Less vegetation. More volcanic rock.

Tom and Wing, the friends who had worked together for the mining company in Liberia, were hiking at their own pace. This is why our group shots only show 9 of the 11 hikers. This is also why ll hikers need five guides, so they can split up if two groups want to hike at vastly different paces. Pole pole and pole pole pole pole. (Photo from Wing)

It was a cloudless and sunny day and we continued to have a clear view of the summit. We crossed the desert landscape in an uneventful hike, until we ascended to a high ridge, where the wind picked up. We had no idea what awaited us on the descent back to 13,000 feet after lunch.

We were headed to the Lava Tower. This is a well-known landmark that several of the main routes pass by. It would be our lunch stop and our first time over 15,000 feet. Until several years ago hikers were able to climb Lava Tower, but it has become unstable.

We left Lava Tower after staying there just under two hours. The clouds started moving in and we lost our view of the summit after two clear days. Our first steps down were into the clouds. This entire side of the mountain was foggy, cold and damp with lots of vegetation and running water. It was hard to believe we just stepped out of the desert. The trees looked like we had stepped into a Dr. Seuss book.

After about two and a half hours of hiking down through the clouds we arrived at our camp. It was completely fogged in, but by 9:30pm it was completely clear again. With the fog gone, we spent several days above the clouds.

Lots of the gear that the guides and porters use has been donated by previous hikers. At the end of the trip, they make it easy for you to donate anything that you don’t want to use any more. I noticed that one of the guides had a water bottle from a computer consultant that also had an Oracle logo on it. I had to get a picture.

Day 5

from Barranco Camp (13,044 ft) to Karanga Camp (13,106 ft)

1.86 miles

4:50 hours

We left camp at 9:00am and after a short hike through the greenery, we reached the rocks. From our camp we could see the notable feature we were hiking towards: the Barranco Wall. It was a rocky ledge that we had to cross, with one extremely narrow spot called the kissing rock. You are so close to the rock you are practically kissing it. Although our guides renamed it the hugging rock for our group of hikers. This was everyone’s favorite day of hiking because it included more challenging hiking and some rock scrambling.

Me Hugging the Barranco Wall (Photo by Nate)

One of the interesting things about hiking on terrain like this is that it is similar to the game of telephone. There are better places to put your feet when you are climbing on these kinds of rocks. The guides have taken these trips many times and they know the trails well. They can also see where the best foot placement is. The first person behind the guide tries to put their feet in same spots as the guide. I hiked in that spot and tried hard to follow his steps. The person behind me could watch my feet and try to match the placement. But as you get further and further away from the guide, the steps no longer follow the guide’s. And just like telephone, these steps are interpreted by each hiker, but it may be influenced by the hiker’s height or even how close they are to hiker in front of them. Since this was not a treacherous hike, there was no need for everyone to match footsteps, so they did deviate very quickly.

Hiking above the clouds (Photo by Tom)

Michael is now a freshman at the University of Virginia and he climbed the mountain with his dad, Mike, to honor his friend, Dylan, who died of cancer. (Photo by Bill D)

The summit is still a long way off. Throughout the course of the day, clouds would pass in front of the mountain as if it were playing hide and seek with us. (Photo by Nate)

This was the most varied day of hiking. We woke up amidst some greenery and then hiked up and over some of the rocky parts of the trail. We crossed an alpine desert to get to a high ridge over a valley with the last running water on the way to the summit. This meant the porters had to come all the way back here to get water over the next couple of days.

Over the course of the week our levels of privacy with each other completely changed. At the beginning of the trip we took many steps off the trail to pee, hid behind trees, rocks and bushes. By this point we weren’t doing much more than taking a step or two off the trail and turning so we wouldn’t splash the trail.

We climbed another ridge to get to our camp above the clouds around 2pm. We ended the day at the same altitude we started, around 13,000 feet. This was our third night camping at this elevation. Our hiking days were getting shorter as we were resting up for the big summit push.

Day 6

from Karanga Camp (13,106 ft) to Barafu Camp (15,331 ft)

3.11 miles

3:10 hours

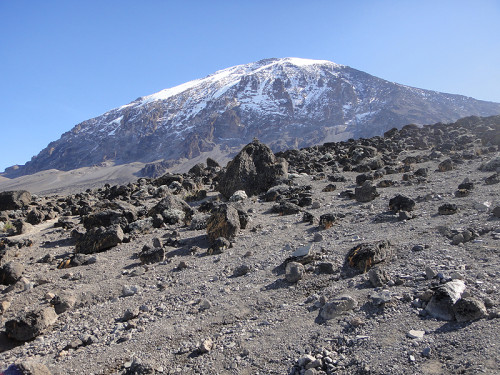

This was the beginning of the most physically challenging 24 hours of my life. It was a clear morning and the Kibo summit was out in all of its glory. In less than 24 hours we would be standing on that summit over 6,000 feet above camp.

We left camp around 9am and beginning hiking up. There were about 3 miles and 2,000 feet of elevation through the alpine desert to cover before lunch. It was a long, steep, slow hike. On this part of the mountain we encountered a totally different type of volcanic rock. It was nothing like the rough, pumice-style you normally think of, but it was smooth and thin, as if the lava flowed in sheets and just broke up over time.

We had a great view of the Mawenzi peak, the second volcanic cone on Kilimanjaro. We arrived at camp a little after noon and lunch was at 1:00. That was when we would learn the schedule for the rest of the day and what we should wear, besides everything we brought. Our base camp was pitched at a pretty steep angle. It was the only place we stayed where it really felt like we were on the side of the mountain.

After lunch we rested. During our rest time, Emily finished knitting her hat. At 5:30 we got up for dinner and our health check. We had soup, spaghetti with vegetable sauce and crepes for our last full meal before our summit climb. I tried to eat as much as I could. I would definitely need the energy.

With the stress of the last health check out of the way, we learned more about the upcoming hike from the guides. In addition to our five guides, three porters were promoted to summit porters and they would be joining us on the hike to the top. That’s eight people supporting 11 hikers on this summit. They were not carrying gear. There was no food to prepare. Just be there for us.

We were congratulated for making it to day 6 and base camp. With the way I felt at the beginning, I was glad to be here. But we needed to start thinking about our next hike which would be long, cold, steep, over rocky terrain and in the dark. If we thought our pace was slow up until this point, we would be going slower than we had ever gone. Their job was to get us to top safely, and as there was less oxygen in air as we went higher, our bodies had to work much, much harder. Remember that the oxygen level at 18,000 feet is half of that where you are now. We were going over 1,000 feet higher than that.

They told us not to be shy about letting a guide know you needed help, or even giving up your pack to one of the summit porters. That’s why they were there.

They recommended we wear 5 layers on the top, 3 layers on the bottom, two pairs of gloves and a balaclava to cover our head and face.

And finally we talked about water. It was going to be cold. Very cold. Many of us had camelbak-style water bladders. They told us to drink as much as we could as early in the climb as we could because the water in the tube would freeze, blocking any water from getting through. They told us to take our quart water bottle, put a wool sock around it for insulation and stow it in our packs upside down. Because it would start freezing from the top, we could turn the bottle over and still have water to drink.

And it was now time for bed. The sun was going down, so it didn’t matter that it was only 6:30. We had to get up at 11:00. It took me some time to get to sleep, but I did sleep. We got up, got our things ready and went into the mess tent for hot drinks and some cookies. We had the usual assortment of hot drinks, which included coffee, tea, powdered drinking chocolate, Milo (a chocolate malt powder) and Nido (powdered milk). It would soon be time to go.

Day 7

from Barafu Camp (15,331 ft) to Uhuru Peak (19,341 ft)

2.49 miles

7:00 hours

from Uhuru Peak (19,341 ft) to Barafu Camp (15,331 ft)

2.49 miles

3:30 hours

from Barafu Camp (15,331 ft) to High Camp (13,700 ft)

2.00 miles

1:50 hours

One of the things that I haven’t written much about is the cold. There are two reasons for that. The first is that I have no idea what the temperature was at any point. I am used to checking the weather on my phone, and it was off for most of the climb. When I looked up the temperature at the top of the mountain before I left, it said it was about 20 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s the only thing that I got. The other reason is that for most of the trip it was not that cold. Most of the days were sunny, and we were hiking across open space. Unless it was windy, the days were pretty pleasant. That translates to hiking in only one or two layers, including shorts several times.

Depending on what time we left camp each morning determined how many layers we wore. On earlier days we started with jackets or an outer layer and took them off after not very much hiking. On days when we started later, our jackets were already off.

It was cold at night, but not frigid. There was not a night that was too cold that I didn’t leave the tent to use the toilet tent. Neither Emily nor I used our pee bottles during the night. Others on the trip did. It’s a good thing I never used it, because when I tried using it for water when I got home, it was not air-tight. Things could have gotten messy with this Tanzanian-purchased plastic bottle.

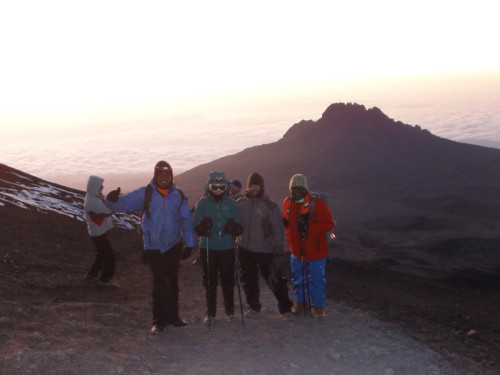

This night was different because we would be outside for hours, rather than bundled up in a sleeping bag. So even if it had not been much colder than other nights (but it was), we needed to dress warmer than we had the whole trip. You can see from the picture above that we had clothes on that don’t appear in any other pictures. I put on nearly everything I brought. Short sleeve shirt, long sleeve shirt, fleece pullover, down jacket, rain jacket, long johns, hiking pants, rain pants, balaclava, gloves, down mittens.

We would be hiking through at least six hours of darkness, so we needed headlamps with fresh batteries. Lithium batteries to make sure they lasted the night in the cold.

At midnight we left camp. Our guides had been pretty firm most of the trip about our departure times, but this one couldn’t slip. We were trying to get to the summit by sunrise. As many times as they had led hikers they knew where the flexibility was. Summit day didn’t have it.

This camp was the steepest we had stayed in, and the first thing we had to do was get out of camp. The steepness of the camp just led right into the steepness of our hike. We were over 15,000 feet and had 4,000 feet to climb in the dark. My headlamp shone a small circle of light on the ground. I focused on that light as I walked.

Pole pole was the theme of this hike. We were going very slowly. We had a very long way to go, and the deterioration of each of us also came slowly. We were running on little sleep and little food, and attempting the hardest climb of the trip. Nothing had really prepared us for this day. But we knew that.

Our chants from the previous days, “Hip Hip, Hop Hop” and “Non-stop, To the Top” were not really working. Call and response only works when there is a hearty response. It was not hearty.

I was drinking as much water as I could, and that meant that every time we stopped for a break I needed to pee. I had to take off my big mittens, take a step or two off the trail to pee, and by the time I was done, we were moving again. As we continued hiking the tube on my camelbak water bladder froze. That meant I had to drink water from sock-covered bottle inside my pack, which took more time on these short breaks. It meant that I was not able to snack on breaks.

During normal hiking, it’s fairly easy to get out a Clif bar and chomp away. If you are using hiking poles, you just hold them in one hand. But in the cold, with large mittens and a face covering, that was just not possible. There was no way to eat while I was hiking. And there wasn’t time to eat during breaks. Our time was not flexible if we were to make it to the top by sunrise. I was getting hungry. Each time I took my mittens off to do something during break my hands got really cold. I had thin glove liners, but it was so cold that after I put my mittens back on, it took some time for my hands to warm up.

As we continued to climb, I started to feel worse and worse. I would not describe it as hard to breathe, because that would make it sound like it was an isolated reaction. Due to the lack of oxygen it was hard to function. Shuffling our feet was the best we could do. Emily and I both gave our packs to summit porters. That decrease in weight on my back helped, for a time.

One of the reasons that we picked this date for the trip was because of the full moon on summit night. Sometimes a full moon lights your way. Sometimes its familiarity comforts you. And sometimes it is just a bright light up in the sky. I remember thinking all of these things as I would occasionally look up at the moon. I never thought that I was out for a stroll on a beautiful moon-lit night. It was cold and we were struggling up a mountain.

Some of this is a bit of a blur, although I distinctly remember thinking I was going to throw up. I also had a gradual, yet building, headache. Most of the hikes until this day were easy-going and in daylight. People were telling stories, chatting, getting to know one another. Not this night. We were pretty focused on that small circle of light put out by our headlamps that illuminated the path in front of us. I heard later that two hikers in our group had intestinal issues on the climb and left their mark on the mountain. I’m glad I was over that and it wasn’t me.

I was thinking that there’s no way I am not going to make the summit at this point, but I just didn’t know how I was going to do it. Each step brings me one step closer. So I take another step.

We finally reached the rim of the volcano at Stella Point. It is 18,885 feet and this is where we watched the sun come up.

Once we crested the rim everything changed. The terrain was no longer as steep. It was also getting light out. Most of the effects of altitude were replaced by feelings of elation. Having made it through the night and only being a short distance from the summit had a strong effect on us. We took some pictures, admired the hanging glaciers and continued on towards the summit.

It was about 45 minutes to an hour up to the summit from the rim. It was still uphill, under 500 feet of elevation, and there was limited oxygen, so we trudged up slowly. I didn’t realize how slowly we were going until we passed another group coming up as we were going down. They still had that zombie, up-all-night look that we must have had.

We reached the summit. 19,341 feet. Hugs. High fives. Pictures. Lots of pictures. The whole group and individuals. There are actually two identical signs to make the picture taking more efficient. It’s pretty cold up there. At least we had bright sunshine. Sometimes it’s cloudy, windy and snowy. You want to leave quickly in those conditions. All we had was limited oxygen. We only spent about 20 minutes on the summit. No picnic brunch. No lounging around.

They call it the roof of Africa. This is the highest point I have ever been to. It will probably always be the highest point I’ll ever climb to. This trip took me halfway around the world and seven days up a mountain. And here I was. At the top of world’s largest free-standing mountain. To say that it was all downhill from here is both a cliche and a reality.

Coming down from the summit back to our base camp took about half the time of going up. Much of it was over scree, which is loose gravel that you can slide on. It’s called screeing, like skiing. It was pretty steep going down. Emily suggested that one of the reasons you hike to the summit at night is because if you saw how long and how steep it was you wouldn’t do it.

We got back to camp and rested a bit before lunch. Now that we had been to summit, the balance of power between the guides and the hikers had changed a little bit. Their job was to get us to the top and now that was done. We were done with health checks. And we could set the schedule. We had been hiking over 10 hours since midnight, so when we were given the option to hike two hours to the high camp or four hours to the Mweka camp, we chose two hours. This would add two hours hiking to the next day, but we could use a break.

We got to camp in the fog and a very light drizzle. This was going to be our last night on the mountain. It was okay if today was a rainy day. An important part of the final night was the tipping ceremony. We decided to all contribute the same amount to the pot and Bill D and Nate would divide it up according to the recommended amounts per position ($20/day for guides, $12/day for assistant guides, $12/day for cooks, and $6/day for waiters, toilet porters, and standard porters) We decided to give a few of the porters a larger tip, including Peter, the toilet porter.

There was a mix of dollars and Tanzanian shillings and it never quite added up. We had sheets with everyone’s names on it, so we listed the amount given. This was a new system that was meant to add transparency to the process, but it wasn’t explained to us well. Michael, our college student, said some thoughtful words as part of the presentation. We all said asante sana, which means thank you. We presented large envelopes of cash to each of the groups (guides, assistant guides, porters, cooks), expecting them to divide it up, but they thought we would divide it up. This was something we suggested could be better explained and managed.

This ceremony also included a rousing version of the Swahili song Hakuna Matata. It’s very different from the version in Lion King. They only dragged one person out to the middle to dance with them. It was me. If they were giving out trophies for the best native dancing by an American, I would not have won. Even as the only competitor. Thankfully, it was already dark by this point, so there is no video of this.

Day 8

from High Camp (13,700 ft) to Mweka Gate (5,380 ft)

8.20 miles

4:50 hours

For our final day, we were hiking back through the rain forest. The only notes I have in my journal for this day are “mud and rain.” It had cleared overnight, so it was sunny as we left camp at 7:30. It gradually got misty, drizzly and then rainy. For the first time all trip, I need my rain jacket for the rain. I even put my pack cover on.

It never rained very hard, but there was enough rain to make mud. A lot of mud. This is the kind of day that you’re happy happens at the end. My pants and shoes were covered in mud. I had plastic bags to pack my shoes in, but the way I dealt with my pants was I gave them away. The guides encourage all the hikers to donate gear that they no longer need, like that Oracle water bottle. It can be used by the guides, porters and even other hikers. My pants were very old and were very big on me. Rather than worry about the mud, I rolled them up when we got back and put them in the donation bag.

Our hike took about five hours on this last day. The climb was over. A bus ride back to the hotel was the only thing that stood between us and our first shower in eight days.

So now is the part where I have to wrap it all up and talk about what this climb means to me. That’s a good question. I’m still looking for the threads of the story nearly two months later as I write this up. It was an experience unlike any other. I spent eight days with 10 other hikers. Nine of them were strangers. When a group of people do something like this together, they bond in a way that is hard to share. We climbed this mountain as a group and there are some stories that just don’t make sense to others who were not there.

A typical meal in the mess tent (Photo by Nate)

Eleven hikers persevered and survived on this eight day journey. It’s not like that plane crash mountain story where they had to eat each other, but survival in a way that is different than our normal lives. Disconnected. Dirty. And a huge sense of accomplishment. How do you tell someone the story of the trip? How do I even answer the question, “how was your trip?” It took me over 8,000 words to write about it.

Some of us were not leaving Africa that next day, but had safari trips planned. Our trip extensions were for different number of days with different itineraries, so we were splitting up. We did run into some of our fellow hikers in a national park and in one of the hotels, so this feeling of camaraderie continued.

We have all connected by email, so it is very easy to remain in touch, but that’s not what happens when we go back to our regular lives. This was a shared moment that is hard to get back to. I will always remember that time I climbed to the roof of Africa with these 10 other people, and I will always struggle to tell the story of those eight days.

Hikers, guides and porters before our final day of hiking